You need to be aware of the revised standard for “harm” from the United States Supreme Court found in Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, 601 U.S. 346, 144 S. Ct. 967

If you’re an employer who has ever been the target of an employee/former employee lawsuit, you’re undoubtedly familiar with civil rights advocates’ (and, coincidentally, plaintiff attorneys) all-time favorite legislation: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)). This statute is simultaneously the triumph of decades – arguably centuries – of heroic efforts by generations of activists fighting for equality under the law, as well as an expensive proposition to defend.

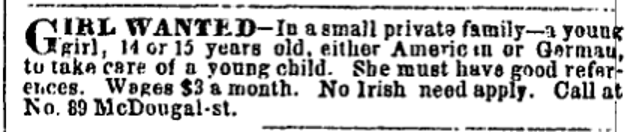

For our part, we’ll take the bad with the good with the bad, as we believe that nuisance-litigation is a small price to pay to protect American workers from workplace discrimination and harassment. The alternative is a world where “Help Wanted” ads reading “[protected category] Need Not Apply” are commonplace, and we know this for certain because, before Title VII, they were commonplace.

New York Times, 1854.

We included this advertisement to remind everyone of the harm Title VII seeks to remedy – and, ideally, to prevent – and that such harm is not a mere hypothetical. We’ve come a long way, but not nearly far enough to take such progress for granted. For a chilling cautionary tale in pictures (all PG/SFW), see https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-47032829. As American citizens, we should all be grateful for the passage of Title VII in 1964.

But as attorneys, we have to acknowledge the fact that Title VII is a disgruntled former employee’s quickest route to a compulsory $10,000 severance package as Title VII provides literally anyone who was subject to termination with a credible threat of months of litigation, especially under the Supreme Court’s new Ames standard, which allows for employee-plaintiffs to claim that they were subject to discrimination by employers with whom they share all protected categories (e.g. race, religion, sex, gender, etc.). See Ames v. Ohio Dep't of Youth Servs., 605 U.S. 303, 145 S. Ct. 1540, 221 L. Ed. 2d 929, 2025 U.S. LEXIS 2198, 2025 LX 198628, 31 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S 15.

The reason Title VII is so easily abused is that half of the elements to a Title VII claim practically satisfy themselves. A plaintiff wishing to establish a claim of employment discrimination of any variety under Title VII – and therefore under its state-level cousin, the Florida Civil Rights Act (Fla. Stat §§ 760.01 et seq.) – must show that:

they belong to a protected class;

they were qualified for the position;

they were subjected to an adverse employment action; and,

they were treated less favorably than a similarly situated individual outside of their protected class.

See Maynard v. Bd. of Regents, 342 F.3d 1281, 1289 (11th Cir. 2003) (citing McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S. at 802, 93 S. Ct. at 1824); see also Knight v. Baptist Hosp. of Miami, Inc., 330 F.3d 1313, 1316 (11th Cir. 2003); Perkins v. School Board of Pinellas County, 902 F. Supp. 1503, 1506-7 (M.D. Fla 1995); Wilson v. B/E Aero, Inc., 376 F. 3d 1079, 1087 (11th Cir. 1087 (11th Circ. 2004).

Simply by existing, you’re satisfying the first element of a Title VII claim, so literally everyone is 25% of their way to a Title VII lawsuit, at all times. The second element is another lay-up, as the very fact the employee was hired in the first place is enough to argue that they were qualified for the position, at least at the pleading stage, which is all you need to survive in order to get to the discovery stage, which is as far as you need to get for a 95%+ chance of achieving a settlement payment. So, a full 50% of a claim for Title VII is satisfied by (1) existing, and (2) being employed in the first place.

The third element used to be where things got at least little tricky, as it required an employer to take some action that imposed “significant,” “serious,” or “material” (collectively “substantial”) economic harm on the putative employee-plaintiff. So, this element specifically required an “adverse employment action” that was both (1) substantial, and (2) monetary. Thus, things like not receiving a preferred work-schedule, or being stripped of convenient-parking privileges, were not actionable under Title VII.

You’re an astute reader, so you immediately noticed the conspicuous use of past-tense in that last paragraph. You see where this is going…… In a fairly recent Supreme Court decision, Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, 601 U.S. 346, 144 S. Ct. 967 (April 2024) the SCOTUS unanimously declared that “adverse employment action” requires neither (1) substantial, nor (2) monetary harm. Rather, “some harm” is sufficient to satisfy the third element of a Title VII discrimination claim.

So, what does “some harm” look like now? Well, things that have been ruled to satisfy the “some harm” standard since Muldrow dropped in 2024 include, without limitation:

requiring an employee to utilize PTO to take a day off for a religious holiday;

placement on a performance improvement plan (“PIP”);

change in duties;

an increase in commute time; and

a placement of a letter of warning in an employee’s personal file, impacting the employee’s future employment opportunities.

You don’t need an attorney to tell you that this is a significantly lower bar to clear than the previous “substantial economic harm” standard. At this point, the third element to an actionable Title VII claim may as well read “my supervisor made a change I didn’t like.” So, as of Muldrow, the only real hurdle to a prima facie claim under Title VII is the last element: a suitable comparator. Thankfully, this element has teeth, even at the pleading stage.

Our own 11th Circuit articulated the importance of identifying a suitable comparator in Lewis v. City of Union City, No. 15-11362, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 8450 *15 – 16 (11th Cir. Mar. 21, 2019):

"Every qualified minority employee who gets fired, for instance, necessarily satisfies the first three prongs of the traditional prima facie case. But that employee should have been terminated because she was chronically late, because she had a foul mouth, or for any of a number of other nondiscriminatory reasons. It is only be demonstrating that her employer has treated "like" employees "differently" - i.e., through an assessment of comparators - that a plaintiff can supply the missing link and provide a valid basis for inferring unlawful discrimination."

This is among the most important Title VII citations American jurisprudence has ever produced. So long as courts never lose sight of this point, Title VII will stay true to its purpose as a bulwark against discrimination, harassment, and cultural backslide.

Philosophizing aside, what the new Muldrow standard means for employers is that treating all employees equally is now the only thing standing between you and an actionable Title VII claim. Thus, implementing and enforcing uniform policies and procedures in your workplace – through employee handbooks, through effective discrimination and harassment reporting and investigation procedures, through effective supervisor training, and through diligent record-keeping – has never been more important. Here’s a good litmus test: if your employees don’t know exactly (1) how, and (2) to whom to report concerns of discrimination or harassment, you might need to shore up either your policies or your training. Either way, it may be time for an all-hands meeting.

There is one piece of good news of employers from the Muldrow case - the higher "significant harm" standard still applies for retaliation claims.

And if all this sounds complicated, well, that’s what we’re here for. Remember that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, so if you have any concerns about discrimination or harassment in the workplace – or if you suspect an employee is planning a dramatic exit and subsequent lawsuit – we’re standing by to assist with whatever you might need.